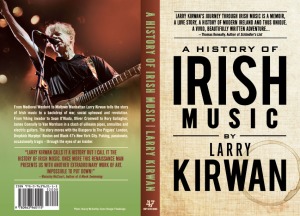

A History of Irish Music, by Larry Kirwan, Forty-Seven Books, 347 pp, $20, ISBN: 980-0963960113

Half a block from Times Square is Connolly’s pub and it’s there that I saw a slight and ginger man give an Irish-American audience a version of ‘Danny Boy’, the memory of which still raises the hairs on the back of my neck. In the Luton pubs and church halls of my youth, all nostalgia had been wrung from the call of those pipes, as each emigrant, identifying with Danny, was called back to the earth wherein their loved ones might even then be waiting for the always belated visit home. The singer in Connolly’s was no stranger to this emigrant love of the song. One of his first gigs in the USA had been touring as The Great Irish Tenor, Lorenzo Kirwan, ‘four sets a night with “Danny Boy” the opening and closer to each’ (Larry Kirwan, Green Suede Shoes: An Irish-American Odyssey (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2005) page 71). ‘Danny Boy’ had also stalked the early days of Black 47, the group onstage that night in Connolly’s. In its earliest days, the band had been pestered with raucous demands for cover versions: ‘“D’yez not know nothin’ by Christy Moore?” | The next thing you’ll be wantin’ is “Danny Boy”’ (Kirwan, ‘Rockin’ the Bronx’, from Fire of Freedom, EMI Records 1993, Starry Plough Music/EMI Blackwell Music (BMI)). Be careful what you wish for.

Skirling feedback, the singer ground his hips into his electric guitar and gave the blue-collar, drinking crowd a story from their own time and place. Like very many of them, an Irish-American skirting legality, ‘a job off the books doin’ demolition,’ Kirwan’s Danny ‘came over to old New York | From Bandon town in the county Cork,’ and then ‘straight into the Village to check out the scene,’ adopting a manner that caused a foreman to hurl the accusation, ‘Hey Danny Boy we think you’re a fag,’ an insult that was met with violence and the defiant cry ‘You’re never goin’ to stop me bein’ what I am–boy!’ (Larry Kirwan, ‘Danny Boy’, from Black 47, Home of the Brave, EMI Records 1994, Starry Plough Music/EMI Blackwell Music (BMI)). The song recalls the 1980s when such sexual adventuring (‘Doin’ what he wanted, livin’ his dream’) left people open to an unknown and lethal infection, but Danny remained defiant (‘I did what I wanted […] | Hey, life’s a bitch and then you die’). Honouring his many friends who had died of AIDS, the gay and lesbian children of Ireland who first found their freedom in the diaspora, Kirwan’s ‘Danny Boy’ affirms the dignity and integrity of their choices. In another incarnation, as Danny McCorley from Belfast in Kirwan’s novel, Rocking the Bronx (Dingle: Brandon, 2010), the gay builder confides that he can not go back to Ireland: ‘And end up like Madam George on the back streets of Belfast or some fuckin’ nancyboy slinkin’ around Barley Dunne’s down in Dublin. […] There’s sweet fuck all for me back there’ (page 321).

As Kirwan finished his own ‘Danny Boy’, with the first verse of the Fred Weatherly original, many in the crowd were questioning their identification with Danny Boy. Kirwan recalls that Black 47 ‘would get requests not to play this perversion,’ but ‘[a]s far as I was concerned, it was hypocrisy to be for civil rights in Belfast and Derry and be against gay rights in New York and Boston’ (Green Suede Shoes, page 301). Kirwan was at the front of the stage pushing his crotch and guitar towards the crowd: ‘Oh Danny Boy, I love you, love you so!’ There was a noticeable diffidence about the response from many in the first few, moshing rows, blessed with flecks of spit from the snarling Kirwan, ‘love you so, love you so.’ Kirwan held their gaze, thrilling and questioning us all.

For a decade Larry Kirwan has presented from New York, Celtic Crush, a programme of the music and song of the ‘eight Celtic nations and their associated cultures’ (www.siriusxm.com). Skipping impishly between Pandemonium and Pantheon, each week he introduces with personal reflection or historical commentary, about three-dozen pieces. Kirwan is master of many trades. His rock band, Black 47 (1989-2014), both animated and reflected recent Irish-American experience (www.black47.com). His plays include historical pieces such as Mister Parnell (published with four others in Mad Angels: the Plays of Larry Kirwan, New York: Forty-Seven Books, 1993) and autobiographical slices of rock ’n’ roll life in Requiem for a Rocker. More recently, he has produced, Hard Times, a musical based on the songs of Stephen Foster, Irish-American author of such folk standards as ‘My Old Kentucky Home,’ ‘Jeanie with the light brown hair,’ ‘Old Black Joe,’ and ‘Oh Susannah.’ His own memoir, Green Suede Shoes is the story of a life of music and politics, and his novel, Rocking the Bronx takes an Irish immigrant and educates him in the ways of 1980s New York city, with its drugs, sexual adventure, polyphony, and ex-pat politics. Mix music and history, stir, and serve as a political cocktail.

Kirwan was born in Wexford and for much of his childhood was raised in the home of his grandfather, Thomas Hughes, an ardent republican who insisted that Michael Collins had betrayed the Catholics of the North by abandoning them to the tender mercies of Presbyterian bigotry. Kirwan’s youth rattled with the battle of ideas produced by his own oedipal defence of the romantic Collins against his radical grandfather. It rang too with the promiscuous musicality of his city and family. Kirwan’s own father was an ocean-going sailor who brought back from his voyages in South America, not only a fierce skepticism of Catholic autocracy, but also a love for tango and calypso. Sailors such as his father and great-grandfather ‘added their store of foreign experience to a town that already considered itself cosmopolitan; and like many before them they brought back the music they had heard in foreign ports and sowed its seed in the fertile lanes and back streets’ (A History of Irish Music, page 11). In his memoir, Kirwan had celebrated the ubiquity of music in Wexford, perhaps even rescuing the Irish rain from cliché:

Wexford was mad for music and if you cocked an ear you could hear it everywhere. Music ricocheted around the streets like errant hailstones, bouncing off slated rooftops, tattooing cobblestones and concrete alike, dissolving in the gurgling gutters that hung haphazardly to the eaves of the houses; you could hear it careen down rickety drainpipes and flush through sewers to the ever-waiting Slaney River. Sit on a bollard by the edge of the crumbling wooden quay and you could catch melodies as they tumbled into the harbor, slicing their way through the silty channels to the sea where they would evaporate and dance across the rainbows that followed every shower (Green Suede Shoes, page 35).

This eclectic harmony was threatened by a rock ’n’ roll insurgency. It ‘hit Wexford like a ton of bricks,’ and the libidinal release could not be accommodated by the generous musicality of older folk: ‘The town’s elders wrung their hands in despair, while questions were asked in the local papers about this new generation and the music that was driving them mad’ (Green Suede Shoes, page 37). Peacock teddy boys, back from London with their American 45s, jemmied their way into the ‘sedate dance halls, where only recently dance cards had been de rigueur’ (Green Suede Shoes, page 39). Yet, the revolution was incomplete, or at least it was so extended that many of the music-makers of Irish and Irish-American rock remained fluent in the promiscuous musical forms of 1950s Ireland. Kirwan lays great stress on the legacy of the showband era. As a teenage recruit to Elvis Murphy’s Liars Showband, Kirwan learned ‘any tune that had entered the Top Twenty as counted down every Sunday night on Radio Luxembourg,’ which would include ‘rock, jazz, swing, folk, polka, tango, shimmy-shimmy, Watusi,’ as opportunities for the Irish audiences to ‘jive, waltz, foxtrot, shuffle or just plain stagger around’ (A History of Irish Music, page 55). The showbands served as a jukebox:

This may have had something to do with the technical prowess and sheer musical electicism of such showband alumni as Van Morrison, Rory Gallagher, Tommy Makem, Pierce Turner, Henry McCullough of the Joe Cocker Band and Keith Donald of Moving Hearts. For unlike those who got their start in garage bands and mostly tended to play in the keys of E and A, or folkies who could turn to a capo, a showband ‘head’–as he was commonly known–had to know his way around every key in which a Top Twenty song was performed. Added to this, Irish horn players preferred, whenever possible, to play in the keys of C, F and G, necessitating that we guitarists match them a tone lower in the finger twisting chords and scales of B♭, E♭ and F (A History of Irish Music, pages 55-56).

Kirwan shares a kinship with Van Morrison. For both of them, their family connection with the sea brought them songs in a foreign key, and ‘Van was blessed that his father was a merchant marine and regularly brought home American Blues and Folk records’ (A History of Irish Music, page 89), but whereas Kirwan’s grandfather had kept religion at arm’s length, Van Morrison’s mother was devoted to the evangelical Presbyterianism of East Belfast that had revived the ecstatic Old Time Religion of the American South. Kirwan argues that this religious formation accounts for Van Morrison’s facility with songs of pain and healing:

I could scarcely believe the fervor of that fundamentalist part of town when I was first taken there as a boy. The very streets pulsed with hymn singing on a Sunday morning as communal voices erupted in praise of their Savior across a sacred spectrum that ranged from spired churches to rickety evangelical shop fronts. […] Though Van has traveled many miles, both literally and figuratively, since those evangelical days, I can still hear an echo of that particular pious ebullience the moment he opens his mouth (A History of Irish Music, pages 89-90).

Recalling the anti-Catholic bigotry of some of those East Belfast Presbyterians of the 1950s, Kirwan finds it all the more remarkable that Van Morrison’s musical intelligence and curiosity brought the young man to the home of the Catholic McPeake family where he learned the musical traditions of the other community in Northern Ireland.

The zero-sum deadlock imposed by Protestant political ascendancy was reinforced by the frigid versions of Catholicism and Presbyterianism with which the people of Belfast were afflicted. Kirwan believes that: ‘There is something exuberant and full of life about the Irish temperament that is not suited to the two strains of Christianity that have dominated the country for the past two centuries. Catholic Jansenism and doom-laden Presbyterianism often bring out the worst in Irish people and both have left a profound stamp on our artistic sensibility’ (Green Suede Shoes, page 219). With insight and brilliance, Sinéad O’Connor has suggested that Veedon Fleece (Warner Brothers, 1974) is the nearest Van Morrison got to the pain of the Troubles (Dave Fanning Show, RTÉ Radio 2, 28 November 2007). O’Connor noted the violence of ‘Linden Arden Stole the Highlights’:

And when someone tried to get above him

He just took the law into his own hands.

Linden Arden stole the highlights

And they put his fingers through the glass.

He had heard all those stories many, many times before,

And he did not know nor care to ask.

And he loved the little children like they were his very own.

You say, some day it may get lonely,

Now he’s livin’, livin’ with a gun (Warner-Tamerlane, 1974).

The violence carried through into ‘Who Was That Masked Man’:

Oh ain’t it lonely

When you’re livin’ with a gun.

Well you can’t slow down and you can’t turn ’round

And you can’t trust anyone.

You just sit there like a butterfly

And you’re all encased in glass.

You’re so fragile you just may break (Warner-Tamerlane, 1974).

Although the songs announce themselves as about an Irish emigrant cornered by gangsters in San Francisco, O’Connor hears a story about betrayal and violence, about suppressed stories of brutality and revenge, all animated by Van Morrison’s horror at the carnage abroad in his own Belfast at just that time. The performances are remarkable and intimate, and not at all like the exuberant holy-roller Morrison of such later music as ‘Kingdom Hall,’ which was presumably much closer to the charismatic services to which Morrison’s mother brought him as a child (Essential Music/Universal Songs of Polygram, 1978). ‘Linden Arden Stole the Highlights’ is plaintive, almost apologetic on behalf a man on the run from his past, and ‘Who Was That Masked Man’ adopts a delicate falsetto that matches the vulnerability of the cornered fugitive.

Larry Kirwan returns to Morrison’s earlier album, Astral Weeks (Warner Brothers, 1968), and to the Belfast that Van Morrison left in 1967, on the eve of The Troubles. Several of the songs on the album are explicitly about Belfast. ‘Cyprus Avenue’ is perhaps Van Morrison’s homage to Patrick Kavanagh’s ‘Raglan Road.’ In each, a boy or man, idolizes a girl or woman, seemingly placed beyond their reach by class, and, within Belfast and Dublin respectively, Cyprus Avenue and Raglan Road have the same geographical significance as streets of the proud and wealthy. Kirwan tells us that another of the tracks on Astral Weeks, ‘Madame George’, ‘may be my favorite recording ever,’ and that it ‘reeks of […] the Belfast of the mid-1960’s, that period when time seemed to stand still right before the Troubles re-ignited and changed everything,’ when ‘[y]ou could almost touch the singular sexual repression lurking on the streets of Belfast’ (A History of Irish Music, page 93). The song is coupled with ‘Cyprus Avenue.’ At the start we are again ‘[d]own on Cyprus Avenue,’ and the author recalls the frisson of the earlier encounter, ‘a childlike vision leaping into view,’ but ‘he’s much older now’ (Universal Songs of Polygram International, 1968). Not just older, but less furtive, at least while ‘drinking wine,’ and when seduced by the ‘clicking, clacking of the high-heeled shoes,’ the ‘smell of sweet perfume,’ of Madame George.

I think the seduction is even more explicit in an earlier version of this same song, recorded in 1967 and released in 1974:

And then your self control just goes

And suddenly you’re up against the bathroom door.

The hallway lights, you find, are getting dim.

You’re in the front room touching him (Van Morrison, ‘Madame George,’ T.B. Sheets, Sony, 1974).

Both versions have the singer looking ‘[i]nto the eyes of Madame George’ and maybe suggest that at this moment the singer saw in Madame George his true object of desire: ‘And you think you’ve found your bag.’ The earlier version has the singer making his excuses and leaving, having been given the alibi of drunkenness for his behaviour, ‘we know you’re pretty far out.’ The transvestite seduction is less explicit in the later, officially-released, version. Both versions, in different ways, dramatise the transgression involved, the one by laying on so heavily the alibi of alcohol and drugs (even the production sound is rather like Bob Dylan’s raucous ‘Rainy Day Women #12 &35,’ with its debauched chorus, ‘Everybody must get stoned,’ Dwarf Music, 1966), while the later one drops some of the most explicitly sexual references. Kirwan’s insight is sharp: ‘That’s what “Madame George” captures for me: denial and alienation of many kinds; but also humanity in all its shapes and sizes–accepted, rejected and occasionally perverted–fighting back and demanding recognition’ (A History of Irish Music, page 93). It’s a recognition that I also hear in the song, for, as the singer is leaving, he insists that he’s ‘gotta go | Catch a train from Dublin up to Sandy Row’; that is, straight back to Belfast, back to Madame George.

For Kirwan, the showband moment was not only a musical bridge between diverse styles, not only an advanced musical education, not only a space where the different generations could perhaps still meet and share an evening, but in its demise it was emblematic of the way the Troubles more deeply entrenched the border. The final studio album from Black 47, Last Call (Black 47, 2014), includes ‘The Night the Showbands Died,’ about the murder in July 1975 of three members of the Miami Showband, stopped at an army checkpoint in County Down as they journeyed back to Dublin from a gig in Banbridge. This savage crime was a joint operation between the British army and Unionist paramilitaries. Kirwan names it ‘the day the music died in Ireland’ (A History of Irish Music, page 146) and recalls that: ‘Nothing seemed sacred from that point on; showbands not only hesitated to cross the border, they steered clear of many of the border counties on the Southern side. Live music didn’t die instantly, but hotel discos had already taken root and received a major boost after this horrible event’ (page 147).

At about this time, Larry Kirwan emigrated to the United States and his History engages heroically with the lesions and lessons, the conceits and deceits of the relations between Ireland and the United States, between Irish-Americans and their neighbours. With delicate irony, Kirwan explains that it in the United States he revisited his grandfather’s republicanism, gained a new appreciation of the indignities and injustice inflicted upon the Catholic communities of Northern Ireland, and grew to respect the Irish-American love of their old country. He took new measure of the interdependencies between the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland, and the United States. In pre-Celtic Tiger days, in the times of the Troubles, the conjunctions of past, present, here and there, were configured very differently in Ireland and America. In Mikhail Bakhtin’s sense, the cultures of the two places expressed divergent chronotopes (‘Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel’ [1937-8], trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist, in Holquist (ed.), The Dialogic Imagination: Essays by M. M. Bakhtin (Austin TX: University of Texas Pess, 1981) pages 84-258). Something of this is registered in the accusation of inappropriate nostalgia that many Irish hurled at Irish-Americans at this time, the mid-1970s. Writing of this period in his memoir, Kirwan admits that:

One of the nasty little secrets of the Diaspora is that most native-born Irish do not care for Irish-Americans. They find their new hosts slow, literal, brash, and unfashionable, rather like country cousins with broad accents and even broader tastes. They call them plastic paddies and find their political beliefs naïve and hopelessly out-of-date (Green Suede Shoes, page 171).

Kirwan introduces these prejudices by describing the career of The Clancy Brothers, and in particular a remarkable Dominic Behan song, ‘The Patriot Game.’ In 1957, during the border campaign, an IRA volunteer, Fergal O’Hanlon, had been killed while attacking a Royal Ulster Constabulary barracks in Brookeborough, county Fermanagh. Behan wrote a song about O’Hanlon and released two very similar versions (Songs of the IRA, LP, Riverside, New York, 1957; The Irish Rover, LP, Folklore Records, UK, 1961). To the jaunty tune of ‘The Merry Month of May,’ Behan explained the impulse to fight:

Come all you young rebels and list while I sing,

For love of one’s land is a terrible thing.

It banishes fear with the speed of a flame

And it makes us all part of the patriot game.

Asked for St Patrick’s Day, 2015, to nominate ‘one song that was especially influential or meaningful to him,’ Kirwan replied: ‘I would have to say it’s still “Patriot Game” and especially the version by Liam Clancy [from The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem, In Person at Carnegie Hall, LP, Columbia, USA, 1963]. Clancy’s delivery is chilling and still a thing of wonder. Which begs the question of why political songwriting is either so obvious or anemic of late?’ (John Donohue, ‘Listening Booth: Black 47’s Larry Kirwan,’ New Yorker, 17 March 2015). The song was one of four recorded by Black 47 on their first visit to a studio (Home of the Brave, cassette, 1990; also released on Bittersweet Sixteen, CD, Gadfly Records, 2006; Rise Up: The Political Songs of Black 47, CD, Black 47, 2014).

Over two famous concerts (3 November 1962, 17 March 1963) the Clancys gave Carnegie Hall two-score Irish songs, poems and tunes. They explained the political context of several songs. ‘The Legion of the Rearguard’ is described as ‘one of the most militant of the Irish rebel songs,’ and the audience are told that the government of the Republic of Ireland had seen fit to ban this song. This is how the ‘Patriot Game’ was introduced on St Patrick’s Day 1963:

It was 1957, January 1st, a cold and stormy day on the border of Northern Ireland, and a little band of men who called themselves members of the Irish Republican Army. (Applause.) They went to … (Prolonged applause.) They were going to take a small barracks up there and by force defeat the British Empire. Unfortunately, there were sten guns waiting for them in the windows of this barracks and two of the men were riddled to death. One of them was a young lad named O’Hanlon who was sixteen years old. This song’s about him. It’s written by Dominic Behan.

The New York enthusiasm for rebel songs came only later to many people in the Republic, and, suggests Kirwan, largely from these live versions, which:

[R]emoved layers of calcification from patriotic laments like Roddy McCorley and Kevin Barry. […] We had become vaguely ashamed of them, especially after the botched IRA border campaign of the mid-1950’s. The Clancys and Makem cauterized some of the innate danger and subversion, thus rendering the old songs more respectable, and ultimately acceptable, by placing them in a more theatrical framework (A History of Irish Music, page 61).

The song explores O’Hanlon’s motives. In the terms used by Louis Althusser (in ‘Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses’ [1970] translated by Ben Brewster in Althusser, ‘Lenin and Philosophy’ and Other Essays (London: New Left Books, 1971) pages 170-86) it shows how the teenager was called out to republican bravery, how he was interpellated as an IRA volunteer. Sceptical of this ideology, Kirwan suggests that: ‘The genius of the lyric is that instead of lionizing O’Hanlon, it mourns his loss while questioning the motives of those who sent him to his death’ (A History of Irish Music, page 61). Certainly, Behan says that O’Hanlon was ‘taught all my life cruel England to blame,’ that it was ‘read[ing] of our heroes,’ and having been ‘told how Connolly was shot in a chair,’ that drew him to the IRA. The Clancys edited this last sentiment. Instead of the story of Connolly inciting O’Hanlon’s patriotism, ‘made me a part of the patriot game,’ they sang instead that the story ‘soon made him part of the patriot game,’ suggesting that perhaps the legacy of Connolly was itself being re-defined, with Connolly drawn into the patriotic game only with hindsight. There is one further revision and one elision that do much more to undermine Behan’s politics.

Behan’s fifth verse trains the critical force of the song not upon those who sent O’Hanlon out to fight but upon those political leaders who had accepted partition:

This country of mine has for long been half-free.

Six counties are under John Bull’s monarchy,

And still DeValera is greatly to blame

For shirking his part in the patriot game.

The Clancy’s dropped the last two lines of this verse and sang instead:

So I gave up my boyhood, to drill and to train

To play my own part in the patriot game.

They also skipped altogether the sixth verse, which in 1957 asserted that:

I don’t mind a bit if I shoot down police.

They are lackeys for war, never guardians of peace.

But yet at deserters I’m never let aim,

Those rebels who sold out the patriot game.

This was doubly scandalous. Not only did it justify the murder of policemen, but it also announced that those who shirked their patriotic duty were legitimate targets, and thus at least implicitly fingered DeValera for assassination. With their emendations, Makem and the Clancys blunted the force of the last verse, since neither traitors nor cowards, nor quislings in the Clancy version, are named:

And now I lie with my body all holes,

I think of those traitors who bargained and sold.

I’m sorry my rifle has not done the same

For the cowards who sold out the patriot game.

On their live recording of 1964, the Dubliners also avoided the sixth (anti-police) verse and they left out DeValera and sang instead of ‘most of our leaders’ being ‘greatly to blame’ (The Dubliners in Concert, Transatlantic, 1965). The Black 47 version of the song excludes the sixth verse, although Kirwan says that he himself ‘definitely didn’t’ know the verse at the time (A History of Irish Music, page 61). Kirwan retains the criticism of DeValera and in the fade-out extends it to a whole string of Irish politicians: ‘DeValera, Cosgrave, Costello, Mulcahy, Higgins, Lemass, Lynch, Fitzgerald, Haughey, sold out, sold out, sold out, sold out.’

Luke Kelly sang an unexpurgated version for a German TV programme in 1966. The difference between Kelly as a solo artist and his role within the Dubliners is also part of this story of the unstable political geography of Irish music. Kirwan celebrates Kelly for taking politics seriously in the manner of Ewan McColl. He describes the attention demanded by and intensity of Kelly’s performance which ‘simply oozed conviction and fixity of purpose’ (A History of Irish Music, page 70). Kirwan laments the loss of this singular voice under the tide of boozy sing-alongs by which Kelly made his living with the Dubliners.

The Troubles produced a new form of political censorship beyond the embarrassment with rebel songs that Kirwan detects after the failed border campaign of the 1950s. In 1971, the government directed that RTÉ should not broadcast: ‘[A]ny matter that could be calculated to promote the aims or activities of any organisation which engages in, promotes, encourages or advocates the attaining of any particular objectives by violent means’ (Mary Corcoran and Mark O’Brien, Political Censorship and the Democratic State: The Irish Broadcasting Ban (Dublin: Fourt Courts, 2005) page 37). The government refused to give RTÉ any advice about the scope of the instruction and as a result the national broadcaster, with something close to a monopoly over daytime radio, gradually stopped broadcasting rebel songs altogether, and that included ‘The Patriot Game.’

This ban severed links between Irish people and their history: ‘a generation of Irish children would grow up relatively unaware of songs that up until then had been part of the DNA of Irish culture’ (A History of Irish Music, page 132). Irish musicians had little encouragement to engage with the Troubles. Only the bravest continued to do so, and folk like Christy Moore earn Kirwan’s respect thereby. Sustained by his colleagues in Moving Hearts, Moore grew in political stature: ‘At a time when most politicians seemed ineffective at best and morally craven at worst, the band filled a void and assumed a stature that few groups of musicians attain’ (A History of Irish Music, page 211).

But, by this time, Kirwan was in the United States where the Irish-American community had suffered no such censorship, and their community was continually leavened with refugees from the violence and injustice of Northern Ireland. On 1 March 1981, the second set of hunger strikes began and with the men suffering towards death, Irish Republicans in New York began to hold vigil outside the British consulate. Kirwan goes along and finds a vibrant republicanism, flourishing beyond the dead-hand of twenty-six county apathy. This might perhaps have felt like atavism were it not for the fact that the injustice of British rule, and of Protestant ascendancy, was made evident each day in the rasping witness being borne by Bobby Sands and his twenty-two fellow hunger-strikers:

What I saw on the green line outside the British consulate was a folk memory and even a hatred brought back to life. These people weren’t misled. Far from it! Many of them were reliving the fears, anxieties, and loathing of those who had been thrown off the land, discriminated against, or denied a proper education’ (Green Suede Shoes, page 172).

The central character in Kirwan’s Rockin’ the Bronx, probably expresses Kirwan’s changing understanding of the Troubles although Kirwan was surely never as naïve as Sean:

I had grown up with no interest in politics, but I had been singed by an ancient relentless flame. Sands’ fate was out of my hands, but he had sparked something visceral that had lain dormant inside me. […] I would not require a blood sacrifice in return, but neither would I ever again wear apathy as an ironic or lethargic cloak (Rockin’ the Bronx, pages 310-11).

And after Sands had died, Sean is pulled into a historical identity, an interpellation, that he had resisted ’ere then:

Bobby’s sacrifice wiped away many layers of colonial and modern conditioning and […] made me aware of their corrosive effect on my personality […]. If I felt, on the one hand, lighter and more aware, so too did I feel a weight of oppression that I had been spared up until then (Rockin’ the Bronx, page 318).

Sands’ resolution hailed Kirwan also, calling him to a new solidarity, not only with the Catholics of Northern Ireland, but also with the Irish-Americans whose grudge in exile now seemed all the more understandable.

This is where Kirwan moves centre-stage in his own narrative for, after giving up his rock ’n’ roll career for playwriting in the mid-1980s, he returned in the late 1980s with a more resolutely political musical practice. From 1989 and for the next quarter-century, he led Black 47 into the lives and imaginations of Irish America. Irish America began to demand that its domestic political leaders engage the Irish Question. Black 47 campaigned to prevent the extradition back to Northern Ireland of a Republican prisoner, Joe Doherty. The group dramatised the integration of Irish Americans with people of colour in their neighbourhoods, and the fusion of reggae, trad and rock ’n’ roll has made ‘Funky Céilí’ one of their most popular songs (on Fire of Freedom, EMI Records, 1993). Musically somewhere between the Clash and Dexy’s Midnight Runners, sweaty like the live Bruce Springsteen, and able to turn an anthem like the very best festival band, Black 47 opened for the Pogues, played Letterman, Leno, O’Brien and Fallon, and conducted themselves with an integrity and abandon that sustained their audiences over a quarter of a century. With his friends, Kirwan told the truth to power and, always more difficult, told it also to their fans. After 9/11, Kirwan and Black 47, gigged even more intensively, inflating their fans and recuperating New York with music. But they were also very suspicious of Bush and his hyper-patriotism and when they came out against the Iraq war, they alienated a good share of their blue-collar audience.

On 15 November 2014, Black 47 played their last gig. On that night, he introduced Danny Boy as follows:

Kinda weird to think, I wrote this song twenty years ago and Irish gay people are still not allowed to march under their own banner in a St Patrick’s day parade. I got one message for those people with the parade. Open up, let some air in. We’re a big people. We handled the Know-Nothings. We handled 9/11. We can handle change (‘Black 47 “Danny Boy” at BB King’s in NYC,’ Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ldROGUPoOk).

Irish music has been a rich resource for handling both change and tradition. Kirwan’s book and his body of work with Black 47 are testimony to both. On a recent show for SiriusXm (6 June 2015), Kirwan played his own ‘Danny Boy,’ and, reflecting upon the success of the referendum to allow gay marriage in Ireland, he followed the song with a message of congratulation back to his own home country. Equality Yes.

Gerry Kearns, June 2015

Pingback: Geographical Formation: Larry Kirwan | The Geographical Turn

Pingback: Borders and Residencies | The Geographical Turn